Archaeological And Historical Analysis

Pennsylvania Colonial Iron Production at Elizabeth Furnace

Elizabeth Furnace, in Brickerville, Pa. is a classic example of an 18th century iron plantation. Apart from its high degree of archaeological preservation, the site contains 13 original standing structures, with few modern alterations. Since 1775, the property has been owned and continually occupied by the Coleman family, who value the property's historical significance. Furthermore, an extensive documentary record for the furnace survives as do numerous examples of its product. In short, Elizabeth Furnace provides an excellent opportunity to study 18th century iron production.

Iron Production

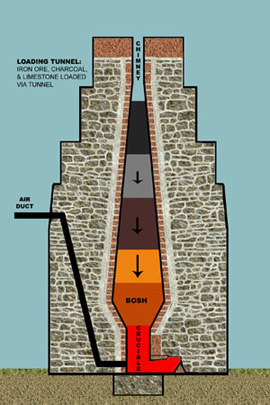

Iron production in the 18th century required an abundance of natural resources, skilled labor, and support teams to provide the wood, ore, food, and maintenance needed to keep an iron furnace community functioning. Elizabeth Furnace was a charcoal burning furnace, like all furnaces of the colonial period, which required vast tracks of wooded land to provide it with a steady supply of charcoal. The furnace itself was constructed out of large sandstone blocks several feet thick. The stack was approximately 30 feet tall and 25 feet wide at the base. The hollow interior of the stack was lined with fire clay and was an oblong diamond shape. The top was approximately 18 inches square which expanded outward to approximately 7 foot wide in the middle of the stack, known as the bosh. At the chimney's base was the crucible, which tapered down from the bosh to a diameter of about three feet. This unique shape focused the bulk of the heat on the iron at the base. A combination of iron ore, charcoal, and limestone flux was loaded into the furnace from the top via the chimney or a loading tunnel cut into the top of the furnace stack. A fast flowing furnace race ran

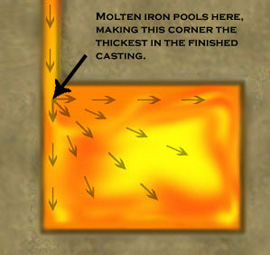

Once a bulk of molten iron was prepared, casting could take place. The type of casting was largely contingent on the quality of the molten iron. If the molten iron was not of sufficient purity, the iron was tapped directly from the crucible and allowed to flow through a trench dug into casting sand. This long feeder trench in the casting

Once a bulk of molten iron was prepared, casting could take place. The type of casting was largely contingent on the quality of the molten iron. If the molten iron was not of sufficient purity, the iron was tapped directly from the crucible and allowed to flow through a trench dug into casting sand. This long feeder trench in the casting

Elizabeth furnace sent its pig Iron to Charming Forge several miles

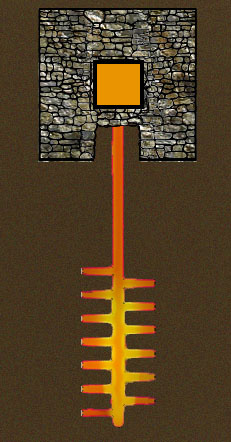

Casting using quality molten iron was done in the casting house adjacent to the furnace. Complex castings, like stove plates, kettles and pots required more preparation than simply digging a few groves in casting sand. For castings like stove

Casting using quality molten iron was done in the casting house adjacent to the furnace. Complex castings, like stove plates, kettles and pots required more preparation than simply digging a few groves in casting sand. For castings like stove

Goods Produced

While the methods of iron production that were in use during the 18th century may seem crude by modern standards, the range of goods they could produce was considerable. Ledgers from the furnace and surviving examples of its products demonstrate the capacity for producing complex, multi-stage castings. One surviving example of such a casting is the Stiegel made "Cannon" stove produced at Elizabeth furnace in the 1760's. While only two examples of this style stove survive today, they are a testament to the capabilities of these early furnaces. This stove is composed of three cylindrical, hollow, sections of varying size. Each section of the casting was cast as a semi-circular portion necessitating six separate castings were then joined together. The three legs of the stove were then cast separately as were the doors, its hinges, and interior plate. Such a casting requires greater skill, than the casting of a flat iron jam stove. It also shows the furnaces ability to cast objects that were hollow, which increased market potential dramatically.

While the methods of iron production that were in use during the 18th century may seem crude by modern standards, the range of goods they could produce was considerable. Ledgers from the furnace and surviving examples of its products demonstrate the capacity for producing complex, multi-stage castings. One surviving example of such a casting is the Stiegel made "Cannon" stove produced at Elizabeth furnace in the 1760's. While only two examples of this style stove survive today, they are a testament to the capabilities of these early furnaces. This stove is composed of three cylindrical, hollow, sections of varying size. Each section of the casting was cast as a semi-circular portion necessitating six separate castings were then joined together. The three legs of the stove were then cast separately as were the doors, its hinges, and interior plate. Such a casting requires greater skill, than the casting of a flat iron jam stove. It also shows the furnaces ability to cast objects that were hollow, which increased market potential dramatically.

Elizabeth Furnace plantation records from the later part of the 18th century give us unique insight into just how broad a range of goods the furnace was capable of producing. Apart from bar or pig iron which was shipped to Charming Forge for use, the furnace was able to produce: 5, 6 &10 Plate Stoves, Kettles, Pots, Pans, Cannon Stoves, Irons, Flat Irons, Dutch Ovens, and Bell. Such items were produced largely for domestic consumption, sold locally and throughout the colonies. Heinrich William Stiegel owner of the furnace saw potential for profits in specialty markets as well, and began advertising in the Pennsylvania Gazette, that he could produce the types of iron goods needed by the West Indies sugar trade.

"Iron Castings Of all dimensions and sizes, such as kettles or boilers for pot-ash works, soap boilers, pans, pots, from a barrel to 300 gallons, ship cabooses, kackels, and sugar house stoves, with cast funnels of any height for refining sugars, weights of all sizes, grate bars, and other castings for sugar works in the West Indies, & are all carefully done by Henry William Stiegel, iron master, at Elizabeth Furnace in Lancaster County, on the most reasonable terms. Orders and applications made to Michael Hillegas in Second Street, Philadelphia will be carefully forwarded."

Recent excavations conducted by Millersville University at Elizabeth Furnace have yielded numerous other artifacts that support the conclusion that it was producing for more than simple or utilitarian castings. Among the artifacts recovered from the Fall 2005 excavations were, a portion of a 1765 Stiegel stove plate, a piece of grape shot cast as ordinance for the Continental Army, ornate stove legs, and other stove plates. The current property owner is also in possession of the original wooden molds used to cast a fence that still encircles his house. In short, the furnace was capable of casting a wide variety of objects, both utilitarian and decorative.

Markets for Iron Goods

Elizabeth Furnace produced a wide variety of castings because it participated in the colonial economy on several levels; as an isolated and self-sustainable frontier community, as a part of the local economy, as part of the regional economy, as well as part of Colonial Trans-Atlantic trade. For instance, while the furnace plantation was located in a relatively isolated frontier area, which necessitated plantation-style food production comprised of several tenant farms on the property, it did rely on the surrounding community to some degree. Because furnace required vast amounts of wood to supply the furnace with charcoal, ironmasters would therefore hire local farmers to cut wood for them on furnace owned land or from their own land. They were paid for their work in either cash, barter for a furnace product, or more often through trading for goods from the furnace company store. The store served as a frontier trading post trading items like shoes, knives, utensils, clothes, or even liquor. Thus, many people in the area surrounding area came to the store to shop or trade. In exchange, Stiegel and other furnace owners got a cheap and constant supply of the cordwood they needed to keep Elizabeth Furnace in blast. Ledgers record many such transactions of furnace resources for furnace goods. While trade with the local community may have been sufficient to keep the furnace in blast, it was not large enough to offer any market capable of making the furnace a successful financial venture. Where then were the sustaining markets that made iron production profitable?

The larger regional market had a greater demand for iron goods, especially in the more populated areas surrounding Lancaster, Reading, and Philadelphia. Iron goods like stoves, kettles, and pots were shipped to these more metropolitan areas and sold at substantial profits due to the higher demand. Henry William Stiegel employed agents like Michael Hillegas to take orders for products from customers in Philadelphia. These orders were then communicated back to Stiegel via letter, who would then produce and ship the ironwares to his customers in Philadelphia. Many of these orders were for specialty items, made to the customer's specifications. Mass produced utilitarian wares like kettles, pots, and stoves were sold to shopkeepers in these areas who in turn sold them in their stores. This regional market comprised the bulk of the trade in which Elizabeth Furnace engaged. Ledgers indicate that most of the furnace's castings were sold to customers or retailers in Lancaster, Berks, and Bucks counties as well as Philadelphia. This was the market that provided the demand for the largest variety and volume of furnace castings; however, it was not inherently the most profitable market.

Some of Elizabeth Furnace's products did not end their journeys in large colonial cities like Philadelphia. Bar iron from Charming Forge was shipped from Philadelphia over seas to London, England. An Elizabeth Furnace ledger details the shipment of 69 1/2 tons of bar iron shipped to London in 1765. Further entries suggest that Elizabeth Furnace did in fact supply iron ware for the West Indies sugar trade, producing the large iron vats used in sugar production in the West Indies as the 1769 Pennsylvania Gazette advertisement indicated. While records about Elizabeth Furnace's trade with the West Indies is less specific than those for regional trade, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that for a short time in the late 1760's and early 1770's Elizabeth Furnace engaged in a profitable trade with the West Indies in specialty ironwares like cast iron pots that could hold several hundred gallons, boilers, and specialty stoves. This trade in specialty ironware conceivably opened the region to Elizabeth Furnace's more utilitarian wares as well.

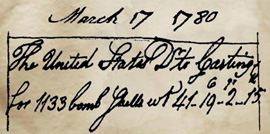

In the late 18th century during the American Revolution the available markets shifted from overseas to the national arena, where the demand for military iron goods was high. Elizabeth Furnace Plantation became one of the first government sub-contractors producing ammunition for George Washington's colonial army. For example, a ledger entry from March of 1780 records the production and sale of 1,133 bomb shells for the colonial army. While the new government could offer little in terms of monetary support to such vital war industries, there were able to supply the vital furnaces with cheap labor in the form of captured soldiers. After the battle of Trenton, Robert Coleman the new owner of Elizabeth Furnace arranged a deal, in which he received 70 captured Hessian prisoners as laborers to work the furnace, and to dig a ditch which would increase the water flow to the furnace bellows and consequently the production of the furnace. Coleman found cheap labor for his business and the colonial government received vital ammunition for its war with Britain, monetary compensation for the use of the prisoners, plus the added benefit of not having to pay for the upkeep of the prisoners. Such arrangements were an intelligent method of sustaining the profitability of the furnace in a time when political circumstances had closed foreign markets. Thus, the national market proved to be a suitable substitute for the foreign ones until they once again became available after the war.

In the late 18th century during the American Revolution the available markets shifted from overseas to the national arena, where the demand for military iron goods was high. Elizabeth Furnace Plantation became one of the first government sub-contractors producing ammunition for George Washington's colonial army. For example, a ledger entry from March of 1780 records the production and sale of 1,133 bomb shells for the colonial army. While the new government could offer little in terms of monetary support to such vital war industries, there were able to supply the vital furnaces with cheap labor in the form of captured soldiers. After the battle of Trenton, Robert Coleman the new owner of Elizabeth Furnace arranged a deal, in which he received 70 captured Hessian prisoners as laborers to work the furnace, and to dig a ditch which would increase the water flow to the furnace bellows and consequently the production of the furnace. Coleman found cheap labor for his business and the colonial government received vital ammunition for its war with Britain, monetary compensation for the use of the prisoners, plus the added benefit of not having to pay for the upkeep of the prisoners. Such arrangements were an intelligent method of sustaining the profitability of the furnace in a time when political circumstances had closed foreign markets. Thus, the national market proved to be a suitable substitute for the foreign ones until they once again became available after the war.

Conclusions

Pennsylvania iron production at Elizabeth Furnace was a technologically and economically demanding endeavor. While it would appear to the modern observer that production was limited by the technological level of their craft, it seems that if a profitable enough market arose the furnace was able to adapt to meet the new demand. The adaptive nature of Elizabeth Furnace allowed it to participate in trade in the local, regional, national and trans-Atlantic markets, making it able adapt to market changes, and shifts. The variety ironwares produced at Elizabeth Furnace made it capable of supplying many different people and places with goods, and its economic success was not contingent on one specific market. The ability of the ironmasters to transition to new markets when old ones disappeared allowed the furnace to survive and thrive, before, during, and after the American Revolution and continue to remain a competitive part of the iron industry until the mid-19th century.

1 - Sieling, J. H. "Baron Henry William Stiegel", Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society 1 (1869): 46. Beck, Herbert. "Elizabeth Furnace Plantation," Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society 69 (1965): 35.

2 - Beck, Herbert. "Elizabeth Furnace Plantation," Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society 69 (1965): 33.

3 - Beck, Herbert. "Elizabeth Furnace Plantation," Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society 69 (1965): 33.

4 - Beck, Herbert. "Elizabeth Furnace Plantation," Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society 69 (1965): 34.

5 - Beck, Herbert. "Elizabeth Furnace Plantation," Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society 69 (1965): 34.

6 - Beck, Herbert. "Elizabeth Furnace Plantation," Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society 69 (1965): 34.

7 - Tyler, John. Letter to Jeff Driesbach, 4 March 2003. Concerns the authenticity of a Stiegel "Hero" stove plate.

8 - Heiges, George L. Henry William Stiegel: The Life Story of a Famous American Glass-Maker. Manheim (Pa): George L.

9 - Stiegel, Henry William, Cannon Stove, 1760's, Jeff Dreisbach Collection, Lancaster (Pa).

10 - List compiled from Stiegel and Coleman Ledgers of Elizabeth Furnace, 1765-1780 (Not a complete list)

11 - Heiges, George L. Henry William Stiegel: The Life Story of a Famous American Glass-Maker. Manheim (Pa): George L.

12 - Statement based on Elizabeth Furnace Ledgers 1762-1765 and 1769-1771, Currently in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania: Call #212

13 - Statement based on Ledgers 1762-1769, archived in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania: Call #212

14 - Statement based on Ledgers 1762-1769, archived in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania: Call #212

15 - Heiges, George L. Henry William Stiegel: The Life Story of a Famous American Glass-Maker. Manheim (Pa): George L.

16 - Heiges, George L. Henry William Stiegel: The Life Story of a Famous American Glass-Maker. Manheim (Pa): George L.

17 -The Coleman Papers, Lancaster County Historical Society, Coleman Elizabeth Furnace Ledger 1780, March 17, 1780, pg. 187 Beck, Herbert. "Elizabeth Furnace Plantation," Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society 69 (1965): 40.

18 - Sieling, J. H. "Baron Henry William Stiegel", Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society 1 (1869): 60. Beck, Herbert. "Elizabeth Furnace Plantation," Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society 69 (1965): 38.

19 - Beck, Herbert. "Elizabeth Furnace Plantation," Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society 69 (1965): 38.