Atlantic World Research

The Perot Site

The Perot Site, located in the eastern portion of Southampton Parish, Bermuda, was the last of the three sites tested during the Summer of 2007. While the Perot had significant Philadelphia ties during the 18th century, with a branch of the family immigrating there during the War for American Independence, their connections to the owners of Elizabeth Furnace remain tangential. They are primarily relevant to this research because of their familial and economic connections with the Stiles and Dickinson families, discussed previously. Additionally, as the Perot family had outstanding French mercantile connections, being of French Huguenot descent themselves, their trade connections and networks were especially pertinent as regards the potential of the Bermudian familial clans to develop illicit trading connections with French Caribbean sources.

|

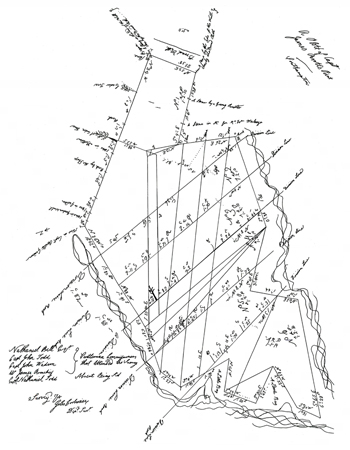

| A plot of land on Perot Point as shown on Public Works Department map, ca. 1750-1790. Many of these land division lines still exist today. |

The Perot Family has a long history on the island of Bermuda, beginning in the year 1740. In that year James Perot Senior arrived in Bermuda from New York, where the rest of his family had settled after having fled France from during the persecution of the Huguenots a generation earlier. His father Jean Perot was from a relatively wealthy family in France, but had fled in the early 1700's to New York with his two children Jacque Perot and Marie Perot to avoid persecution for his Protestant beliefs. Jacques married Marie Cousson in New York and had several children, one of whom was our James Perot Sr. Once in New York, the family patriarch Jacque Perot quickly took steps to regain his footing, and he was evidently successful as his daughter Marie later married into a socially and economically powerful New York family, the Ellistons. Robert Elliston, Perot's son-in-law, was the New York Comptroller of Customs, a connection that presumably placed the Perot family in good position participate in the Atlantic Trade.

Despite his family's success in New York, James Perot (son of Jacque) left his home in New York and settled in Bermuda in 1740. Upon arriving on the island he established himself as a goldsmith and silversmith in Southampton Parish. Interestingly, several of his pieces survive today, including a communion chalice he made that still survives in St. Anne's church. Shortly after coming to Bermuda, Perot married Frances Mallory, daughter of William Mallory who was an influential Bermudian in his own right, in 1742. James then purchased land in Southampton parish adjacent to that of his wife's family home (which today is the core of the Waterlot Inn property). The property Perot purchased eventually totaled about 20 acres and was located primarily on the Point that lies between Jew's Bay and Riddell's bay in the Great Sound.

The current building at 7 Peppercorn Lane appears to have been constructed by James Perot sometime near to the time of his marriage in 1742, though an exact construction date is unknown. A home is shown in roughly the same vicinity as 7 Peppercorn lane on the 1663 survey map drawn by Richard Norwood. Unfortunately Norwood appears to have only crudely mapped in house locations, as he was apparently far more concerned with property boundaries, and thus only drew structures as rough sketches. It was possible, therefore, that an earlier 17th-century dwelling was located on or near the current Peppercorn Lane property. Potentially determining the location of this 17th homestead was one of the goals for our archaeological testing at the Perot Site, and ample artifactual evidence confirmed a 17th-century occupation on the property.

Whilst living in Southampton, James and Frances Perot had 4 sons John, Elliston, William, and James Jr., as well as four daughters Mary (who died in infancy), Martha, Frances, and Angelina. In 1780 both James senior and Frances (nee. Mallory) his wife died of Yellow Fever at Water Lot Inn, the home built by Frances' father William Mallory in 1708. Presumably they relied on their kin to aid them while ill, as by this time most of their children were grown and/or moved away. James and William Perot had gone into business together in Crow's Lane in what is now Pembroke Parish. John and Elliston Perot had gone abroad, acting as merchants in the Caribbean, including Dominica, San Domingo, and St. Eustatius (until the British took the island during the War for American Independence). After being briefly imprisoned in St. Eustatius, John and Elliston Perot moved to Philadelphia, where they set up shop as merchants and intermarried into the prominent Morris family, the owners of one of the oldest distilleries and breweries in the Colonies.

Upon their father's passing, the Children of James Perot Sr. received his lands in Southampton. The property at 7 Peppercorn Lane presumably passed to James Perot Jr., as by this time William Perot was established and had a home called Avocado Lodge in Crow Lane. John and Elliston were living in Philadelphia and were now prominent merchants in North America remaining absentee landowners in Bermuda. Frances Perot was married to William Sears and was living in Smith's Parish and so staked no claim on her father's Southampton lands. Likewise, Martha was married to John Wadson, and thus had no reason to stake her claim on her father's land. Angelina, who appears to have been a spinster, spent most of her life occupying a room in her brother James's house (7 Peppercorn) which was presumably the house left to him by their parents. Angelina's will, proved 1834, indicates that she ended up living in her father's house. Presumably, when James Perot Junior died in 1816, his part of his father's estate, including the house, returned to his James Perot Senior's estate to be divided among his remaining heirs. William apparently continued to renounce his claim. Thus the house of James Perot Sr. fell to his sons, John and Elliston Perot, who were living in Philadelphia. John and Elliston apparently realized that they would likely be unable to give their Bermuda lands to their children since the United States and Great Britain had just concluded the War of 1812, and relations and loyalties between the USA and Britain were tenuous. They decided to pass the house and lands to their spinster sister Angelina, in the hopes of keeping the property in the family.

In her will Angelina Perot passed the property to the two sons of her brother William Perot. The property passed to William B. Perot the eldest son of William Perot, but as William B. Perot had built a home in Hamilton called Par la Ville, he decided in 1880 to sell the Port Royal property to Joseph C. Dickinson. It is at this point that we lose track of the deed record. However, the Savage Survey, conducted in 1899-1901 and the first true land survey of the Island since the Survey conducted for the Somer Island Company by Richard Norwood Survey in 1663, clearly shows a standing house in the location described by the early deeds as the land of the Perots. As a matter of fact, the house, which is now 7 Peppercorn Lane, Southampton, is the only extant property on the whole of Perot point as of 1901. A survey of aerial photographs taken between 1941 and 2006 shows the evolution of the land during the mid to late 20th century. The one element in these photos that remains constant through time, undergoing only mild structural additions, was 7 Peppercorn Lane.

The archaeological testing conducted at the Perot Site concentrated on determining areas of archaeological significance. The majority of the test units excavated were 2x2 test units and shovel test pits, though several 5x5 and one 5x10 unit were also excavated. There were no extant ruins on the property on which to center the excavations, although the standing home contains the original 18th core of Perot's first house. The majority of open yard was located inland on the south-side of the house, so the majority of shovel testing was conducted in this area. These units in the yard failed to reveal any sealed archaeological deposits to warrant further scrutiny, though a strong generalized scatter found here included both 17th and 18th century artifacts, mixed with later deposits.

The area between the house and the bay, less than 50 ft. in most places, provided a smaller area to test. With less ground to cover, larger 5x5 test units were established to take a larger sample. The 5x5 test units placed between the water and the core of the house proved be the richest, and deepest archaeological deposits containing thousands of artifacts ranging in date from the 17th century to the present. The earliest artifact found was an enormous fragment of pipestem, with a bore diameter that places it in the 1600-1650 time frame. In one unit by the house a buried wall was discovered, but proved to be part of a historic landscape feature, not a building foundation as was initially hoped. To the west of the unit where the wall was discovered a deep 5x5 excavation unit was excavated. It contained large quantities of 18th ceramics and glass as well as burned wall plaster and limestone shingle fragments. After extending this unit 5 feet to the east to collect a larger sample it was determined that this feature had been an open stone quarry for wharf block during the 18th century, and that it had been backfilled with the remains of an older structure (possibly the original 1622 dwelling). The use of open pits for trash disposal in the historic period is quite common and accounts for the relative jumble of artifact date ranges present in the units.

This historic backfilling episode also accounts for the lack of a decisive stratigraphic sequence in these units. From these excavation units we were able to determine the source of the original course of stone on the property's dock, and as indicated by the presence of 17th century artifacts determined that there had been an pre-eighteenth century dwelling in the area. The discovery of scraps of brass and copper plating and brass machine cut nails, suggests that they were sheathing their ships on the property, which meant that they were bringing them up to their house and not keeping them in Bermuda's designated ports as required by law. Finding materials for shipbuilding and/or repair suggests docking and unloading at this private residence, and because docking at private residences and coves (and hence not paying customs) was the chief means of smuggling mentioned in nearly every letter of complaint from a Bermuda governor or Comptroller of Customs, this evidence is at least intriguing.

The testing projects at the Perot Site were not strictly terrestrial. The location of the property within a concealed bay, deep enough to allow Bermuda sloops to dock and unload, suggested that evidence of the Perot's trade, legal or illicit, might exist in the water. The sheltered nature of the bay would have minimized the effects of hurricanes and storm surge, leaving the floor relatively undisturbed and allowed to accumulate. Thus a 5x5 testing unit was established just north of the Perot dock, and was excavated until rock was encountered. A variety of ceramics (including French faience) and glass were discovered as well as more modern artifacts. In short the brief nautical testing confirmed that apart from terrestrial middens, the bay also served as a dumping ground and repository for 18th-century artifacts. This brief nautical excavation was also accompanied by a snorkel survey in transects around the bay surrounding the property. However, this survey did not identify any 18th-century remains.